The digital world moves fast. Between your group chats with friends, your online game chats, and your social media, you see a lot of information when you're online. But how do you know what information you can trust to be fact, and what is misinformation?

You can decide what is true – and what's not – by asking questions[1](external link). These questions will help you think about what you are seeing online. They will help you to decide if what you are seeing is there to help you – or there to hurt you.

Who made this – and why?

Making a website or a social media post look legit is easy.

A nice logo, a few sources, and some good pictures. That's all you need to make even the dodgiest information look like it's coming from experts. Add in a .org or a .edu URL and even savvy web users can be fooled.

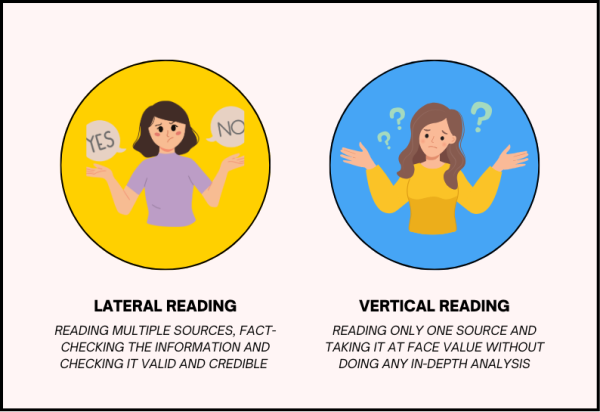

Reading a website or post isn't enough to know if the information in it is factual. To be sure the information you read is trustworthy and reliable it's important to read laterally instead of vertically.

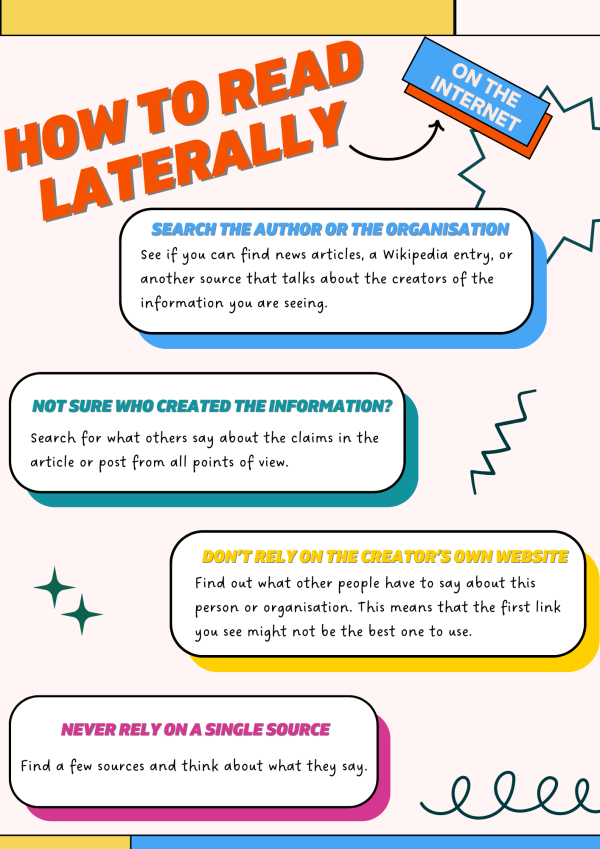

Here's how to read laterally

Open a new tab on your browser, head to your favourite search engine, and see what you can find out.

If you need help finding trusted information online you can ask for help from AnyQuestions, a free, online chat service run by the National Library of New Zealand. Between 1pm and 6pm weekdays, students can log in and chat with a real librarian who'll help guide their research. Librarians also teach valuable information literacy skills so students can learn how to find relevant and reliable information for themselves.

- Visit AnyQuestions(external link) to find out more.

For more tips and advice on figuring out what's real and what's not on the internet, visit Netsafe.

What about bias?

Everyone is biased- it doesn't mean that information from biased sources isn't useful or true. For example, anti-smoking groups share information about the dangers of smoking and vaping. They are very biased – against smoking and vaping. But the information they share is true – and useful.

You also have biases. Think about whether you want a piece of information to be true. If so, be extra careful when deciding if the information is useful or trustworthy. The more we want something, the more we can overlook red flags.

What does the evidence tell me?

Sometimes we have to examine facts to decide if information is trustworthy. Evidence can be a whole range of things. It can include pictures, data, videos, or scholarly journal articles.

When evaluating evidence there are two questions to ask yourself.

Is this evidence reliable?

Think about the source and use your lateral reading skills to decide if it's reliable. Remember reputation and bias are key parts of deciding if a source is reliable.

If the evidence is in a New Zealand newspaper or media source check to seeif they have agreed to abide by the Media Council Principles. These organisations have set high standards for themselves. They still make mistakes, but they have processes to correct them.

Is this evidence accurate

Is the information you're looking at correct? Be suspicious and take your time.

A picture on social media from an unknown account may or may not show what it claims to. Statistics and other data can also be hard to verify. But you can use a few different sources on the internet to check claims and evidence. Use websites like factcheck.org, hoax-slayer.com or snopes.com to check the content and see if it's made up, a rumour or an urban myth.

[1](external link) The underlying information from this section derives from the Creative Commons licensed portion of the Stanford History Group Civic Online Reasoning Curriculum: Digital Inquiry Group (2024) Civic Online Reasoning: Curriculum. Available at: https://cor.inquirygroup.org/curriculum(external link) (Accessed: 27 May 2024).